Tips for Following Screenplay Format

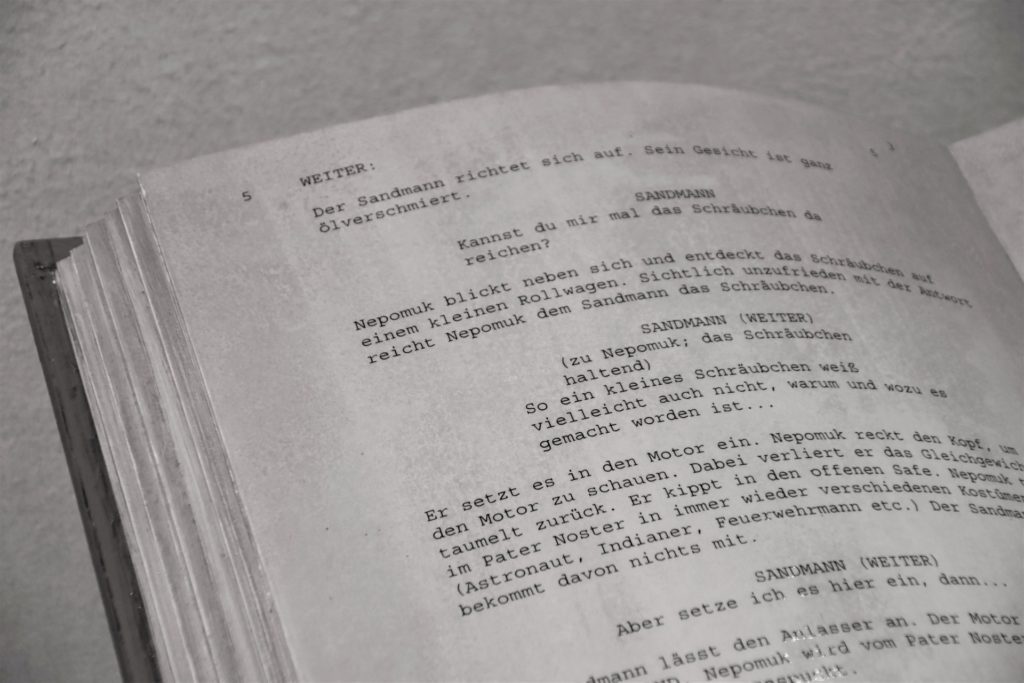

Screenplay Format

“Check out the Big Brain on Brett!” Sound familiar? If you’re a film buff, as every aspiring screenwriter is, of course it does. Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary’s hit script Pulp Fiction made over $213 million in box office receipts and made Samuel L. Jackson and Uma Thurman household names. Tarantino has become a poster boy for writers with dreams of the big screen.

A highschool dropout and broke at the time, Tarantino pieced together the idea for Pulp Fiction while working in a Los Angeles movie store. He had to learn his craft as he struggled to make his way in Hollywood, and even though his style was so iconoclastic that it pushed one studio rep to send an expletive laden rejection, he pushed on. If you, too, have Tarantino dreams of writing a hit script, one thing you will need to learn is how to present your writing in proper screenplay format.

Screenplays are a type of script written specifically for visual forms performed on a screen, such as films, TV, and so forth. Knowing how to format them may seem unimportant to the novice who thinks having a fabulous story is all that matters, but proper formatting is crucial to the people viewing your script and trying to see how it will appear on the screen. A well-formatted screenplay helps producers and directors understand locations, actors, props, costumes, and settings they’ll need. All important considerations as they balance the content of your story against the potential cost.

Laying Out the Story Visually

Screenplays have basic elements that help break down the story into its filming elements. Before you begin writing and shopping your own screenplay, you should familiarize yourself with these elements:

- Scene Headings or Sluglines: Sluglines tell the reader where and when the action is happening. They are presented in all caps and begin with an indication of whether the action is interior (INT) or exterior (EXT) and a note on time of day, such as morning, evening, day, or night.

- Action Lines: Action lines are placed immediately beneath the slugline and indicate what is happening in the scene. They should be concise and visually descriptive. Interior thought should not be included. If you are including notes to how an actor should portray a moment, be sure that it is something they can physically portray, such as “Tony becomes agitated.” You should always capitalize a character’s name when it first appears and can also capitalize important props, camera movements, etc.

- Characters: Character’s names should be centered and capitalized, and once you have identified a character the name should be used consistently for the rest of the script. Beneath the name you will include the dialogue the character speaks and may need to include what are called extensions–V.O. for voice over, O.S. for offscreen–to show how the dialogue will be heard on the screen.

- Parentheticals: These are directions to actors given in parentheses to indicate how the line should be portrayed, such as “(Laughing) or “(Tearfully).” You can also include actions you’d like tohe actor to perform.

- Transitions: You may need to indicate some specific transition between scenes, such as CUT TO, DISSOLVE TO, or INTERCUT. These are only used when you want the cut to stand out, not to direct the way each but should be formatted. Transitions are capitalized and placed flush right on the page.

- Other devices: You may need, at times, to indicate other elements. Film shots can be indicated in the script (sparingly) as can other special specific moments such as montages, chyrons (which are onscreen indicators of location, time, etc.), and, for TV end of act indicators that show when a script will go to commercial. A special case is when you include lyrics. A page of script is assumed to be a minute of film, but music moves more rapidly, you may thus need to interlace lyrics with descriptions of action or the general mood of the sequence in order to space them out to equal the one-page formula.

What to Avoid

Certain pitfalls may announce you as a beginner and make the reader less likely to engage with and ultimately accept your screenplay. Avoid these mistakes to make your script as presentable as possible;

- Scene description should not be over elaborated: Focus on concise visual action descriptions and avoid ornate language, particularly when it’s not visual.

- Don’t overdo parentheticals: While you have a vision for how your script is to be performed, you need to allow for directorial and actor interpretation. Stick to what is absolutely necessary for the scene.

- Use transitions sparingly: In the same vein as parentheticals, film editors are professionals who make decisions on the most effective means of transitioning from one scene to another. Unless transitions are crucial to indicate, leave it to those who have made it a career.

- Use film shots sparingly: Directors and cinematographers make decisions about camera shots. It’s better to describe the way you want the action to be seen on the screen and let professionals make the camera decisions.